Rachel Roberts

This marks the end of Week 1. We’ve decided for this month that we’ll each contribute about a paragraph to a weekly ‘wrap up’ blog post.

We’re in Singapore working with Earth Observatory of Singapore to create a prototype for a new game about responding to disasters (specifically, volcanoes and typhoons) and managing evacuation procedures. We’ve been given a very detailed brief (thanks to Finig for coming over to Singapore a year ago to flesh out that proposal) and so have been able to dive right in, making games and systems models.

I’ve taken a slightly different approach to my own involvement for this project – rather than stressing about trying to know everything I possibly can about the system, I’m letting go of that and embracing not knowing. Instead, I’m trying to think and create mechanisms that are clear, engaging, hopefully even elegant. There are experts here who can tweak the science if it’s off a bit.

Nathan Harrison

I’ve spent a lot of this week thinking about how the system revolves around two key decisions – the decision of the government to order an evacuation, and the decision of the individual to evacuate.

Each of these decisions has a lot of complex factors and influences, and together they house many of the concepts we want to try and communicate in this project.

So unlike Best Festival Ever, a system with many points of management, and Democratic Nature, with a wide range of system features, it feels like this game hinges on those two decisions. I’m interested in how we can explore those decisions, through multiple iterations and changing perspectives, to illustrate the larger system. I think it’s a great opportunity to try new types of games.

Nikki Kennedy

Week one is done and it feels like I’ve not got through very much at all. I love reading about disaster management but feel like I have barely scraped the surface.

This week I have been quite interested in how we simulate memory of past events in our audience – or if we even need to. If you live in a volcano or typhoon prone area then you’ve either experienced an event, or an evacuation, some form of training/disaster preparation or even just stories of what happened. But if you’re an audience coming into this show/game then you might not have that experience, or have an experience but of a disaster in a specific location/conditions. Our fictional or based-on-real environment is unlikely to be one you’re familiar with and therefore you need to have some familiarity and connection with it.

I feel like you do need this grounding in past events if only to streamline experience for the participants and make the operation of the system seem more logical. If each audience member has a different idea of how the system works in a disaster situation then it’s much easier for them to find fault in the structure or the system represented – and to miss the points being illustrated. It’s not crucial to the process, but it does limit the ‘noise’ or contest-ability of the limits of the system, and allow for the point and focus of what we’re trying to explain to be easier to understand then it’s probably worth it. It might make our job a bit easier.

There is so much to be of interest right now – we’re trying to work out structure and all the things about disasters and disaster management and reactions we could gamify – as well as how to make this into something easily transportable and for just one facilitator – but reducing noise around the game focus is maybe useful for helping to get across a few specific things.

Also the Art/Science Museum was the best. I want nice, safe, comfortable, fun, adult friendly slides everywhere I go.

David Finnigan

This is the first for the second development of our new project looking at natural hazard crises at the Earth Observatory Singapore. I’ve spent a lot of the week digging back into some previous notes from my last stay here, and surveying journal articles that EOS have shared with us.

I wanted to write briefly about one of those articles, because I think it captures a little of the kind of science being done in this field – which is not just the science of how volcanoes and typhoons occur, but the social science that examines how communities and individuals respond to them.

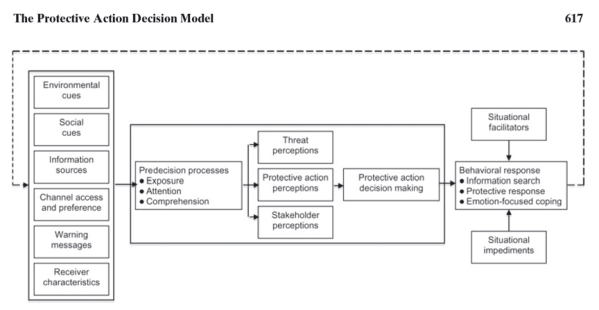

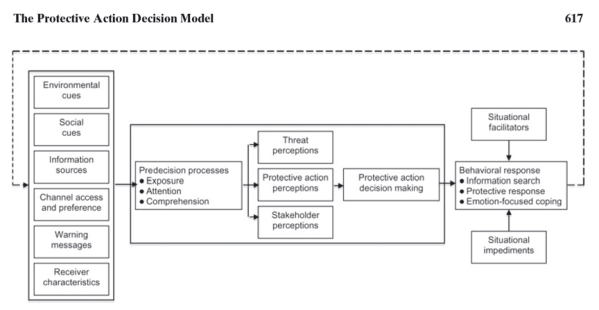

This is from a paper on the ‘Protective Active Decision Model’ – Lindell and Perry attempt to model the way in which humans decide what course of action they’ll take in the face of a natural hazard crisis.

The first thing that happens is the left column – people receive information about the disaster. It might be environmental (they smell the smoke, see the clouds), it might be a news source, it might be socially.

The middle cluster of boxes is a representation of that person’s internal decision-making state. The three big questions that each person (subconsciously) asks when they get this news are:

- What do I understand this threat to mean?

- What are my options?

- What do I think/feel about the sources of this information?

The outcome of this thought process is some or all of the following actions:

- They seek more information about the situation

- ‘Emotion-focused coping’ (they worry)

- They take action

When they seek more information, that means going back to the start of the process.

There are two key ideas from this paper that I took:

- Everyone has a particular set of criteria that they need met before they’ll take action. Those criteria are different for everyone. Roughly, people need six pieces of confirmatory evidence before they’ll do something as drastic as evacuating. (That number might be lessened if the evacuation order comes in the form of the military pounding on your door.)

- This kind of conceptual model is used to capture how people think about disasters so that you can analyse it mathematically, or simulate it in a software model (an agent-based model). It’s useful to know about these kinds of models because they’re how scientists understand and simulate human behaviour in natural disasters.

This is not something that’s likely to be in the show, but I wanted to write about it as an example of the sort of research being done in the field.

Question here: How will we represent people’s behaviour in a disaster situation in our game? Will it be through narrative, or will we use a simple model like the PADM?